I offer this Montana Journal article by Todd Wilkinson about friend Rick Reese who died of leukemia in January at age 79.

I think he was one of the great conservationists in my lifetime.

I had the privilege of hikes, floats and mountain climbs with him periodically during the 45 years I knew him.

Here's is Wilkinson's story, which captures Reese so well:

The Climber-Conservationist Who Literally Put Greater Yellowstone On The Map

As advocates for the Yellowstone region go, Rick Reese ranks right up there with the most impactful of all time. His legacy is written in the abundant wildlife and healthy landscapes we value today

EDITOR'S NOTE AND UPDATE:

Rick Reese passed away on Sunday, January 9, 2022 and our condolences

are with his family and friends. If you've worked with Rick Reese,

climbed with him or joined him in the cause of protecting Greater

Yellowstone, we'd like to hear your anecdotes. We'll share them at the

bottom of this story. Please send them along by clicking on this link.

by Todd Wilkinson

Rick Langton Reese may not be a household name to Mountain Journal

readers familiar with the famous constellation of conservationists

synonymous with Greater Yellowstone. Frankly, if true, the lack of

association is ironic considering that one of the reasons MoJo exists as a watchdog of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is owed to him.

After 35 years of reporting, I’ll assert now that it’s important to provide context for how the term came to be.

Scores

of young conservationists working for various non-profit organizations

and land management agencies in our region today do not know the history

of its rise into common parlance. Many may not be aware of the fact

that, for decades, agencies like the US Forest Service and Bureau of

Land Management stubbornly refused to use the word “ecosystem” in

describing the region because of fear it might undermine their

bureaucratic jurisdictional authority.

Indeed, readers

here may also be unfamiliar with Reese as an influential elder, but he

and his cohort of conservation contemporaries literally put the Greater

Yellowstone Ecosystem on the map—a feat taken for granted but in its day

globally momentous.

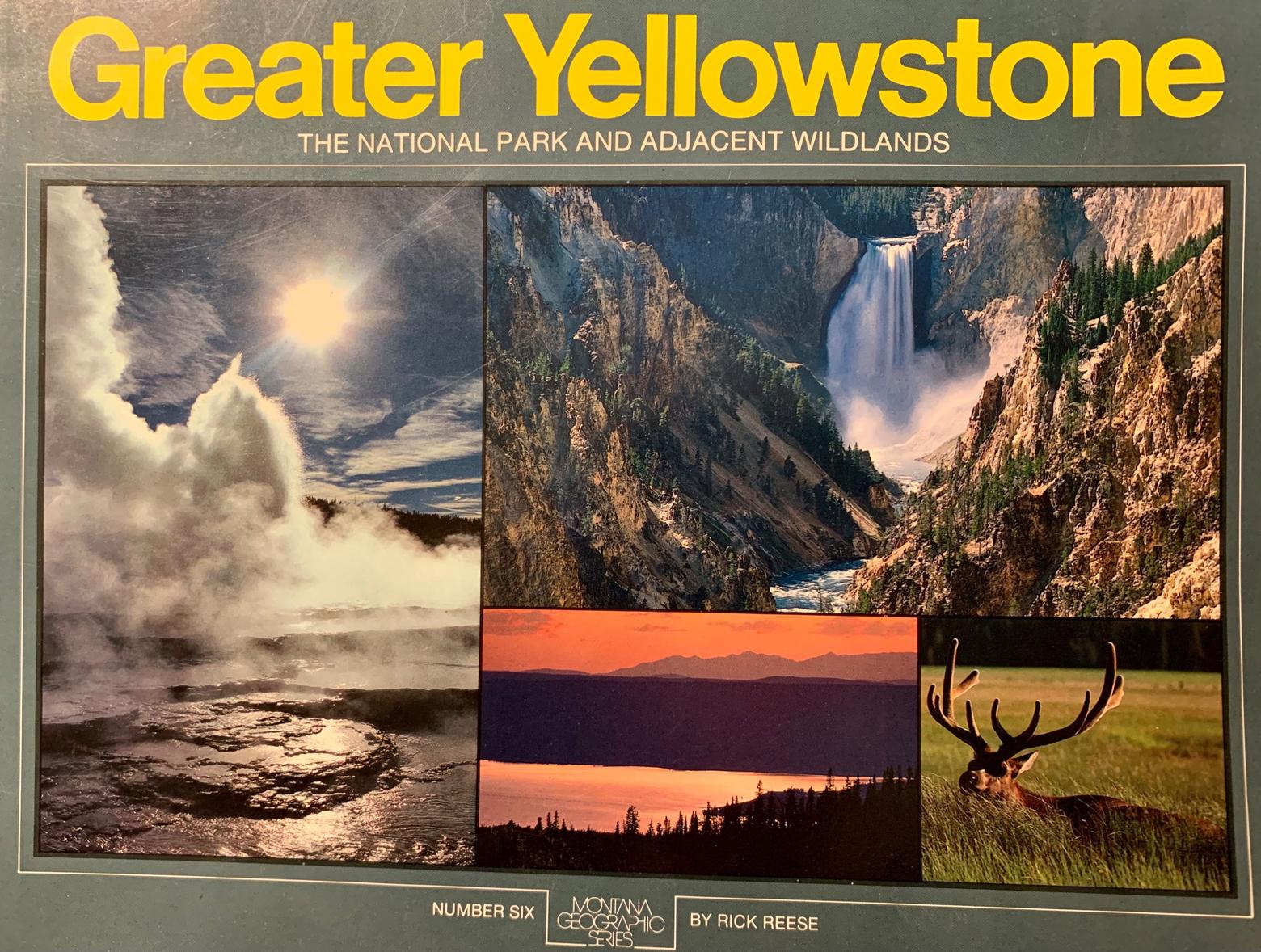

Reese has played not only a seminal

role in popularizing the modern concept of “Greater Yellowstone”—he was

the first to write a book about it—but for decades he has insisted that

whenever possible the three words should always be presented fully in

tandem.

“Greater” as in signifying there is much more happening beyond the primary focal point.

“Yellowstone”

as in it being our first national park, the cradle of an American

conservation ethic that has been emulated around the world, and that its

health is dependent not only on interior factors but forces occurring

around it.

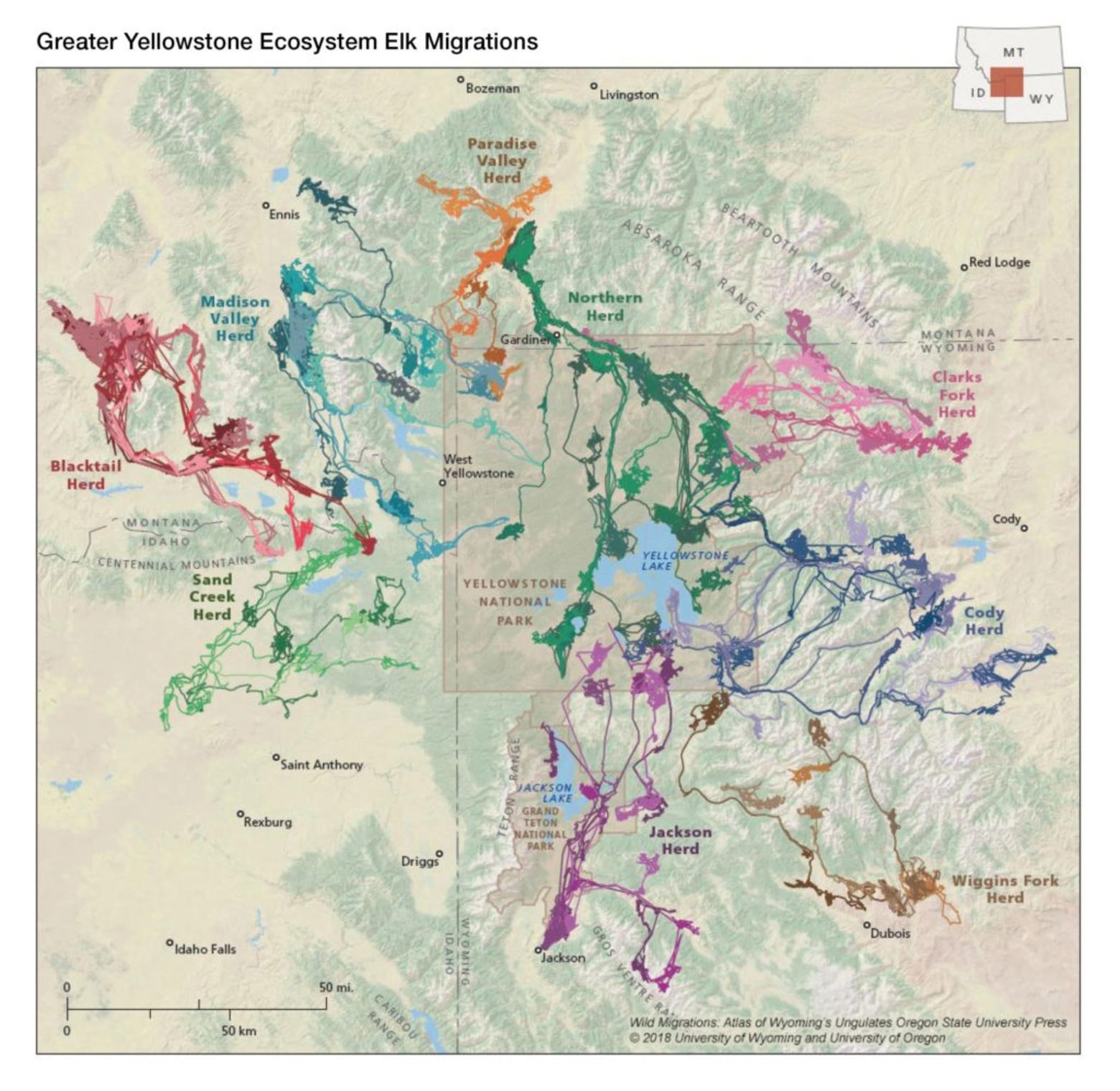

Lastly, “Ecosystem,” indicating this

region of seamless, interconnected mountain ranges, rivers and vales,

wildlife migrations, and scenic landscapes that stir our imagination, is

analogous to a human body. The rivers of Greater Yellowstone are like a

circulatory system moving around water, the essential lifeblood;

wildlife migrations are equivalent to a pulmonary system and mountains

and vales, encompassing public and private lands, serves as essential

bone and connective tissues. Underlying all of this is a

geo-hydro-thermal system that is manifested as geysers, hot springs and

fumaroles, some 10,000 in Yellowstone, that represent the largest

still-functioning congregation of those phenomena on Earth.

The

Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem encompasses all of the above and many

other moving and stationary parts. What’s extraordinary is that such

things only persist in an interrelated way because they have not yet

been impaired by various kinds of human activity.

One of

Reese’s favorite taglines, that he has uttered innumerable times to

anyone who will listen, is that “the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is

one of the last biologically and topographically-intact ecosystems in

the temperate zones of the Earth.” It’s safe to say that Greater

Yellowstone never had a more tenacious, headstrong and enthusiastic

cheerleader.

It’s safe to say that Greater Yellowstone never had a more tenacious, headstrong and enthusiastic cheerleader.

The

first thinkers in modern times to reference the Greater Yellowstone

Ecosystem were the late grizzly bear biologists Frank and John Craighead

who employed it as a metaphor showing that bears do not recognize human

boundaries drawn on maps. A healthy population of griz cannot exist in

Yellowstone alone and depends upon bruins being able to move widely.

The same applies to all of the other species.

Back in 1983

Reese and a plucky continent of citizens from the three-state

intersection of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho came together and founded the

Greater Yellowstone Coalition. The idea of forming a group started with

Ralph Maughan,

a conservationist and political science professor at Idaho State

University in Pocatello. It was Reese’s book in 1984 and subsequent

editions that made Greater Yellowstone palpable—a focal point that had

previously been lacking.

Reese was born in Salt

Lake City in 1942 and raised in the Jesus Christ Church of Latter Day

Saints. While his involvement with Mormonism lapsed over the years, he

often mentioned how love of nature is a value embraced by many of the

faithful—people he forever welcomed into the fold of conservation.

Right

after graduating from East High School, he joined the National Guard,

his service coinciding with the Berlin airlift crisis. Upon returning to

the states, he earned an undergraduate degree from the University of

Utah and then completed a graduate degree program as a Woodrow Wilson

Fellow at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of

International Studies.

While he would go on to teach

political science as a professor at Carroll College and serve as

director of community relations for the University of Utah, one of his

favorite passions was rock climbing and mountaineering which began

during his youth along the Wasatch Front. He was recognized as a skilled

and precocious young alpinist.

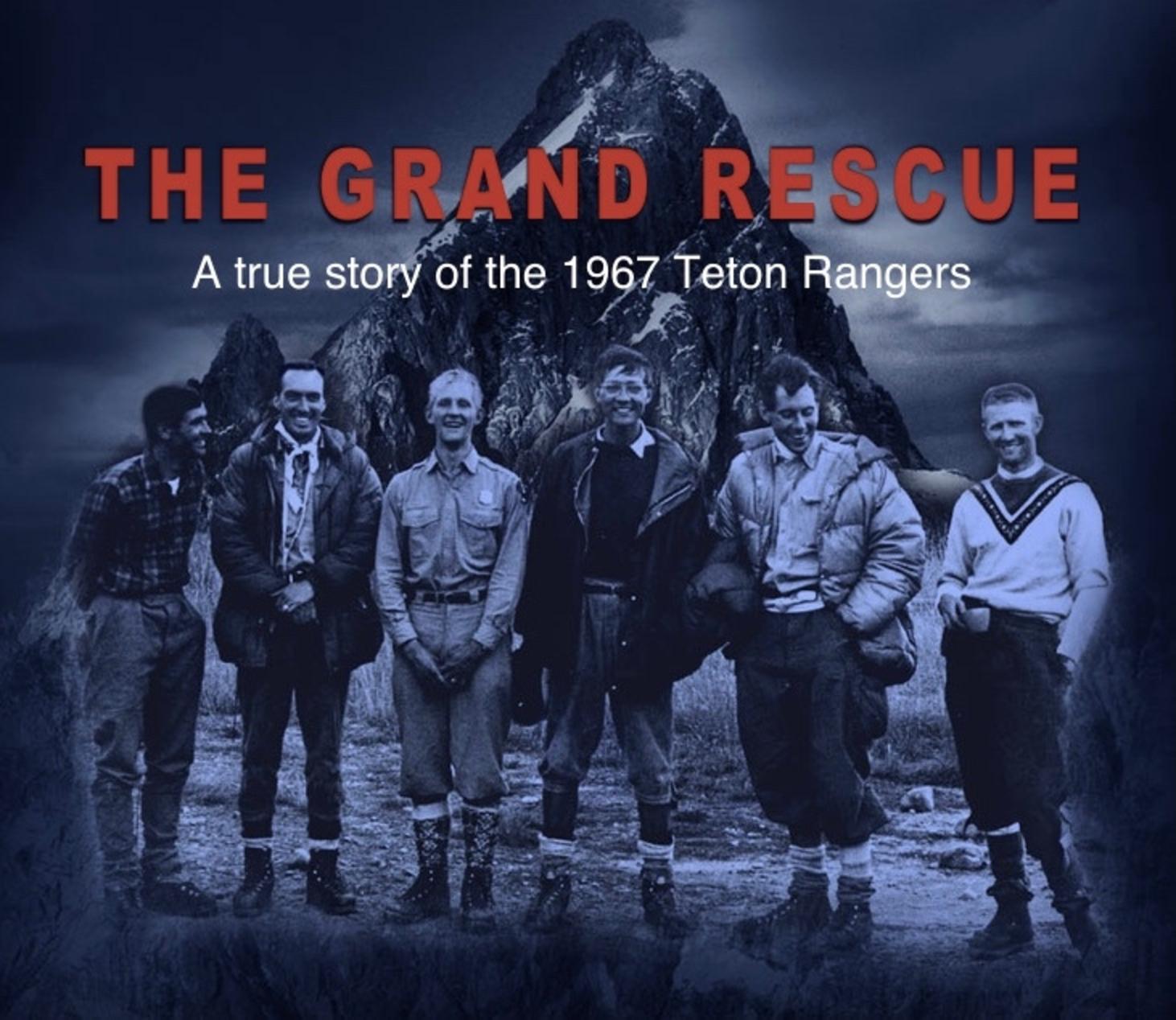

Reese became a member of

the crack Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers in Grand Teton National Park,

taking part in several dramatic rescues, none more legendary or

harrowing than his involvement with six friends who rescued a severely injured climber and his companion on the North Face of the Grand Teton.

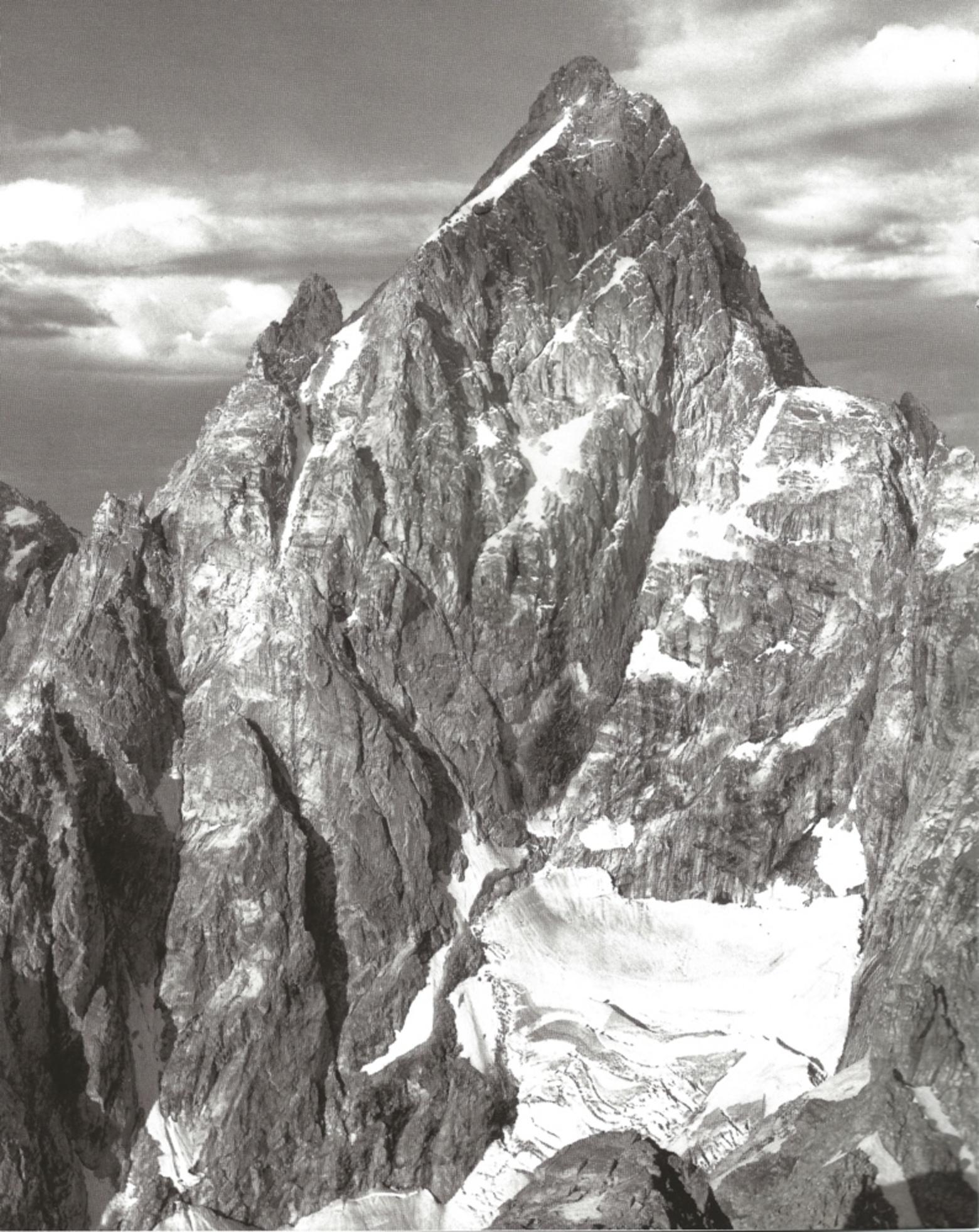

Above:

the treacherous North Face of the Grand Teton, where climbers are

constantly dealing with falling rock, was a perilous place for a

three-day, two-night rescue. It is remembered in a film. Just above:

Reese and five of his six legendary climbing amigos—not pictured is

Leigh Ortenburger who took the photo. Photo of North Face of Grand Teton

courtesy National Park Service

The event featured in a documentary, The Grand Rescue,

that appeared on PBS stations across the country. You can view it at

bottom of this story. His close alpinist friends who took part were Pete

Sinclair, Leigh Ortenburger, Ralph Tingey, Mike Ermarth, Bob Irvine and

Ted Wilson who went on to become mayor of Salt Lake City. Reese himself

has gone on climbs around the world and is considered a mentor to

people one, two and three generations younger.

It was in

1980, however, that he and his wife from New Mexico, Mary Lee, made a

life-changing decision that brought them squarely into the center of

saving the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. That year the couple was

recruited by Yellowstone Park Superintendent John Townsley to serve as

co-directors of The Yellowstone Institute (today Yellowstone Forever),

which offered outdoor education opportunities to park visitors. It led

to a close friendship with Townsley and every superintendent since but

most importantly discussions of how to protect the integrity of

Yellowstone and lands around it.

Just a few years later

the Reeses were part of meetings held in Jackson Hole, Bozeman and at

the ranch of John and Melody Taft in the Centennial Valley where the

Greater Yellowstone Coalition was born, in 1983. Reese served as

founding president for two years and has remained a lifelong supporter,

including serving as GYC's interim executive director.

Among

his many honors is a lifetime achievement award from GYC and his

papers, correspondence and documents relating to his life as a

conservationist and climber are today part of the Montana State

University Library’s Special Collections

Reese in the Andes of Patagonia in 2005

If you’ve been following the news, America lost both Edward O. Wilson and Thomas Lovejoy in this last week of 2021, giant thinkers of large landscape conservation within hours of one another. Not long ago, we lost Michael Soule,

godfather of conservation biology; and around the Greater Yellowstone

region within the last year or so we’ve mourned the passing of Jean Hocker (pioneering figure in the land trust movement), Joe Gutkoski (civil servant, wilderness, river and bison defender), Bert Raynes

(Jackson Hole naturalist), Tad Sweet (resident of Henrys Lake, Idaho

who advocated for protecting the Centennial Valley), Blackfeet elder Earl Old Person, conservationist-public radio talk show host-social critic Brian Kahn, Jim Posewitz (civil

servant, and quintessential sportsman who, among other things, stopped a

dam from being built that would have swamped under Paradise Valley,

Montana). There are others too numerous to mention.

So

many conservation heroes worthy of emulation never enjoy the full praise

they deserve for the contributions they make while they are alive.

Being

an advocate for nature, staking out tough positions often unpopular

with the status quo, can be an unpleasant space to inhabit in a world

full of conflict-averse citizens contented to do nothing, or take the

course of least resistance. While Reese has lead by keeping his cool,

being an idyll of poise and gentle persuasion, he has a thick spine and

says that none of the monumental achievements that make Greater

Yellowstone extraordinary would exist without conflict.

“People

who don’t understand the value of wild country, or who don’t care, or

who want to capitalize on it for their personal gain, will take as much

as they can get. They are always demanding more of something that is

finite,” Reese told me. “The takers need to be met with an equal amount

of resistance from people who are not willing to surrender or give away

things that, once gone, cannot be replaced.”

The first

time I met Reese was at Lake Lodge in Yellowstone where the Greater

Yellowstone Coalition was holding its annual meeting. I was a young

journalist.

Saying no to thoughtless development can earn

one enemies, derision and alienation even though, in the eyes of future

generations, you are much revered as an ancestor, he told me. Reese

often reflects on the actions of US Sen. Lee Metcalf of Montana, who was

a friend of Reese’s, and who pushed for creation of the

Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness that straddles Montana and Wyoming and

would have been half as large, or less, unless Metcalf had been an

advocate for more. There’s also a wilderness named after Metcalf in the

northern reaches of the Madison Range.

What the public

today does not understand, Reese says, is that Metcalf pushed for more

wilderness protection because citizen advocates gave him the cover to

act and think boldly. Conservationists did not kowtow to the forces who

wanted to settle for less. In recent years, Reese the elder helped

jumpstart a growing groundswell of citizen support for protecting

230,000 acres of the Gallatin Range as federal wilderness.

Everywhere he went in Greater Yellowstone, Reese inspired others.

A few autumns ago, as a founding MoJo board member, Reese and I and a group of his board colleagues went to his original hometown of Salt Lake City.

Among

the delights was spending time with Rick as he offered a guided tour of

the Lake Bonneville Shoreline Trail that skirts the Salt Lake metro

along the outline of ancient Lake Bonneville, a late Pleistocene

paleolake. While he was working at the University of Utah, Reece helped

lead the effort to get a recreation trail established that would enable

people in Greater Salt Lake to stay fit and rub up against nature.

People

will protect what they love but love comes from being familiar with a

place or a creature, he said as part of the belief system that he and

Mary Lee had evolved while they were leaders of the Yellowstone

Institute. Long before E.O. Wilson popularized Erich Fromm's term biophilia—humankind’s

love of nature—the Reeses witnessed it firsthand while overseeing the

operations of the Yellowstone Institute devoted to educating visitors

about the natural history of Yellowstone.

Reese also

helped fledge an entity called the Yellowstone Business Partnership

designed to show how conservation stewardship of natural resources and

not maximizing their exploitation was good for ecology and economy. He

has constantly been cloud seeding conservation and even helped

ecologists Lance and April Craighead secure funding to complete a

wildlife assessment in the Gallatin Mountain Range which concluded that

native animals will need plenty of space in the future as the effects of

climate change and human impacts deepen.

I

owe much of my Greater Yellowstone education to Rick. We all do. He's

been ahead of his time and a messenger just right for ours. Reese played

a key catalytic role in the creation of Mountain Journal.

Five winters ago, he and Mike Clark, former executive director of the

Greater Yellowstone Coalition and a conservation advisor, approached me

about launching a new journalism entity focused on Greater Yellowstone

and using it as a lens for thinking more broadly about wild nature in

the WestThe concern expressed then by Reese and

Clark was that the conservation movement was going soft and losing its

ability to inspire. Just as people won’t protect what they don’t love,

Reese said journalism plays a vital role, as an important as any

conservation entity, in making the public aware of threats.Covering these things has been a priority of MoJo.

“Journalism plays an important role in not only alerting readers to

problems and explaining why, but waking people up,” Reese says.

Reese astutely believed that MoJo

would draw a crowd of avid readers, but he and Clark had no idea how

large our audience would be or how much resonance our stories would have

with lovers of Greater Yellowstone coast-to-coast and around the

world. Even they are amazed at MoJo having 230,000 followers

on Facebook, readers in 200 countries and stories that have been

circulated in front of tens of millions.

As we lionize

people like EO Wilson, who, by the way, became a fierce advocate for

protecting the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem thanks to groundwork laid

by Reese and others, Reese deserves his own place in the pantheon,

alongside others like the Muries of Jackson Hole, Len and Sandy Sargent of Cinnabar Basin, river conservationist Bud Lilly, the Craigheads and many more fearless advocates.

History

is destined to remember Rick Reese as a person who always looked ahead

past the span of his own life to see the higher purpose. He has not

fought for wild country because it’s popular in the short term, but

because it is right. We all owe him a debt of gratitude for helping us

see the brilliance of a Greater Yellowstone.

Rick

Reese on top. A few years ago, Black Diamond shared this photo of Reese

along with the caption and using it as an opportunity to praise him for

his conservation work, including working to protect fragile geological

formations in his native Utah. This photo, however, was taken in the

Tetons. Wrote Black Diamond: "Local Badass. Climbing Legend. Supporter

of conservation Rick Reese (then 73 years old) gears up with Steve Moore

for the CMC route on Mount Moran in Grand Teton National Park. In 1976,

Rick was referred as the team's strongest climber for the Jenny Lake

Climbing Rangers and he's still getting after it." Photo courtesy

Savannah Cummins

Rick

Reese on top. A few years ago, Black Diamond shared this photo of Reese

along with the caption and using it as an opportunity to praise him for

his conservation work, including working to protect fragile geological

formations in his native Utah. This photo, however, was taken in the

Tetons. Wrote Black Diamond: "Local Badass. Climbing Legend. Supporter

of conservation Rick Reese (then 73 years old) gears up with Steve Moore

for the CMC route on Mount Moran in Grand Teton National Park. In 1976,

Rick was referred as the team's strongest climber for the Jenny Lake

Climbing Rangers and he's still getting after it." Photo courtesy

Savannah Cummins

No comments:

Post a Comment